By

Leslie O'Flahavan

|

Date Published: August 10, 2020 - Last Updated August 05, 2020

|

Comments

The blue summer sky darkened to charcoal gray. Lightning cracked once, then twice. On the second crack, our power went out.

As the minutes ticked by slowly in the dark, humid house, I used my time the way anybody who’s obsessed with customer care would do: I pictured the hectic scene in the power company’s contact center, with 17,000 in-the-dark customers clamoring for help all at once.

Sitting in my kitchen, trying not to think about the chicken defrosting dangerously in the freezer, it occurred to me that the power company’s social channels probably carry a higher volume of contacts during an outage. If your cell phone battery is charged, and you need to complain because you’re bored and sweaty, Twitter may seem like just the place to be. I vowed, “When my electricity comes back on, I’m going to study how well power companies respond to customers’ tweets,” and so I have.

I’ve reviewed the Twitter customer care conversations of about 20 power companies, and my “research” has led to a wonderful discovery: Many of them are writing excellent, responsive tweets to customers! Even if you’re not in the utility biz, you can learn a lot about how to do social customer care right if you take these five tips from these companies:

1. Explain when you’re available to respond to tweets.

Many power companies do not staff their social channels 24/7 for customer care. They want customers to phone in, use an online form, or use their mobile app to report outages or downed lines. I don’t claim to know whether a power company should staff social channels 24/7 for customer care, but I am certain that all companies should explain when they are available, not when they aren’t.

@AEPOhio does this right. Their profile simply states, “We're on Twitter 7am-11pm M-F and 8-5 weekends.”

A Mid-Atlantic power company (see photo) explains their Twitter hours of operation the wrong way. They kind of explain when they aren’t available on Twitter - “Account not monitored 24 hours a day” - but they don’t actually clarify when they are available.

A Southern California company states, “Feed is monitored from 9-9pm M-F and 9-6pm on Saturday,” which undoubtedly causes most customers to wonder, “Feed? What feed?”

2. Show—at least—a modicum of empathy.

Of course, if 17,000 customers come at you with the same complaint, it can be difficult to come up with fresh empathy statements for each one. The best companies try, though, and some do provide sincere responses for distressed customers.

By recognizing the economic hardships caused by the pandemic, @SDGE gives an empathetic response to a customer who’s angry about rate increases: “We know that bill relief is needed now more than ever in light of the stay-at-home order and the financial hardships caused by COVID.”

If you can’t handcraft an empathy response for each customer, at least use the commonplace, acceptable “We understand being without power can be frustrating” wording.

I was sad to see unempathetic tweets from other companies, like this one in North Carolina. They simply replied “Crews are responding” to each customer who reported an outage. I’m sure most power companies rely on templated social media responses when they’re in the midst of an emergency, and that seems reasonable to me, but an empathy statement can be part of the template. It could be worded thus: “We know you’re eager to have your power back on. We are too! Crews are responding. Go to our online outage map to sign up for text updates on when power will be restored.”

3. Be candid.

I do realize that companies can’t be open about all situations, but when you can be open, you should. Candor is essential in social media where customers’ attitudes about your company’s honesty are contagious.

@AEPOhio could have omitted mention of a squirrel that caused the outage, but the tweet that includes this information is much better for having included that fact. The known and somewhat simple cause of the outage makes their promise to restore power in 30 minutes believable.

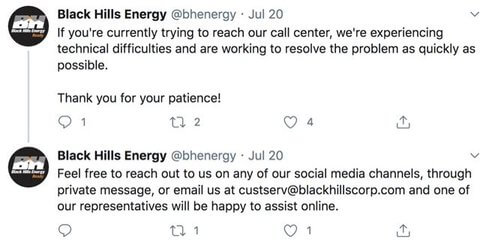

When your company has technical difficulties, be candid. Use the reach and share-ability of social media to admit the problem and offer a workaround, like @BHEnergy does in this example (see photo).

If you can share information, do it! Don’t be less than forthcoming. When this customer complained to a Louisiana power company that he’d been waiting on hold on the phone for 40 minutes to get help stopping his service, they replied that he should DM them his detailed account information, so they could help. While it’s commendable that they’re offering to help him in a second channel, a candid response could have mentioned a reason for the extraordinary wait time, for example: “Last night’s storm caused scattered power outages, so our telephone team is a bit backed up now…” While giving an honest reason for the delay might not matter to every customer, it will assuage some, so it’s worth a try.

4. Explain why you want to move the conversation to the private channel.

Customers are willing and ready to move to DM, but you should mention or imply why you want to make the conversation private. While the direct message isn’t literally a separate channel, it feels more like text than Twitter, and from a customer experience perspective, DM can feel like yet another contact. To offset that feeling, give the customer the reason or outcome of moving to DM.

In these tweets, @AEPOhio gives the customers incentives for the direct message: “I’ll check on your estimated time of restoration” and “I’ll see if a cause has been determined.”

After a customer complains that the power company workers left their gates open—and risked letting their dogs out—@OPPDCares does a good enough job giving a reason to move to a private channel when it writes, “Can you please DM us your address so we can look into this?” A more specific request would have been better: ““Can you please DM us your address so we can follow up with the work crew who came to your home?”

I probably don’t need to tell you this, but it’s never a good idea to be passive aggressive when you suggest the customer DM you. When this New York company writes, “Please DM us the account number if you need assistance” they seem to be ignoring the reason the customer does need assistance, which he explained: an elderly relative received a $900 estimated bill.

5. Stop apologizing for “any inconvenience.”

This wording is beneath your social customer care team because it’s dismissive and vague. “We apologize for any inconvenience this may have caused” is brush-off wording that contributes to customers’ perception that your company doesn’t really care. A non-pology is bad enough in one-to-one customer service conversations via email or on the phone, but it’s worse in social when everyone can see it and share it.

A simple, honest apology like the one pictured here isn’t that hard to write. @NVEnergy apologizes for an outage with “We understand how frustrating power outages can be, and we apologize for the loss of power.”

When @GeorgiaPower uses the word “huge” in front of “inconvenience” in this apology, they rescue that tired word. To the customer, the six power hiccups are a huge problem. Sometimes, keeping it light is the right way to say you’re sorry. @GeorgiaPower gives an oblique but charming apology when they write, “Talk about bad timing!” to a customer who was in the middle of coloring her hair when the power went out.

After seven hours, my power came back on. I had to reset all the clocks, and I had to finish the chocolate ice cream, which was in the perfect state of softness. I’m grateful that the outage prompted me to contemplate my power company comrades’ communication in social customer care. Companies that provide always-on, essential services like these can teach the rest of us—who merely sell turtlenecks, tires, or training—how to write great tweets.